Copied from the Lansing State Journal – MI – Sunday, September 28, 1980

Blind students treated ‘too normally,’ they say

MSB alums rap modern schooling

By Sharon M. Bertsch – Staff Writer

Football teams and broom making, boarding school deviltry and a chance “to be normal” – the Michigan School for the Blind gave all these things to its children.

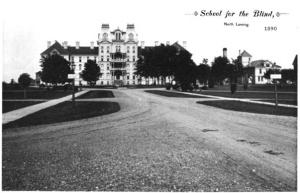

For 100 years, it was the boarding school for Michigan’s brightest blind children.

An American revolution occurred in the 1970s, though. State and federal special education laws moved three-quarters of Michigan’s blind children back to their homes and community schools.

Multiply-handicapped blind children were taken out of mental institutions and sent to school for the first time in history.

ABOUT HALF of the school’s students now are retarded, if only because blindness makes it hard for them to conquer their other handicaps. More than half the 115 students are “severely multiply-impaired.”

Teaching these children is so expensive that the executive branch of the state government is trying to merge MSB with the School for the Deaf in Flint or find a way to cut costs.

Many of the school’s graduates view the revolution with horror.

“It’s a revolution that no one was prepared for,” says poet Lucille Sawyer, who attended the school in 1920-28 and now lives in the Riverfront Apartments.

“Shunted” into public schools, blind children can’t shine socially or in extracurricular activities, many Lansing MSB graduates believe.

The sighted world will “accept an unsighted child to a line, and beyond that they won’t go,” John Noland declared in his wife Erna’s concession stand in the Highway Building downtown.

NOLAND ENTERED the school’s fourth grade in 1920 and left in 1929. His wife finished the last three years of high school there in 1933.

MSB, though, had football, basketball and wrestling teams playing other small high schools like Williamston and Webberville. MSB had marching bands, proms and plays.

School Superintendent Nancy Bryant likes the change. “I would not send my own children away to school,” she has said.

Attending boarding school for years – going home only for summer vacations and perhaps Christmas and Easter – “disenfranchised them from their communities in a sense,” she says.

That’s why the neighborhood around the school has been a virtual “ghetto” of MSB graduates for years, she contends.

Laughter and deviltry transformed a strict school into a home they loved, though.

“We laughed our way through school,” recalls Mrs. Sawyer.

RULES WERE strict. In the early years, boys and girls weren’t supposed to play together or even write a member of the opposite sex.

Boys and girls, as everywhere, though, found ways to get together.

“Oh gosh, there’s all kinds of corners up there. It’s a blessing the school house can’t talk,” Noland joked.

“I don’t think we were any better than the teenagers today,” agrees Mrs. Noland.

Like boarding students elsewhere, they filched the domestic science teacher’s fudge supply and raided a custodian’s cache of Prohibition wine and cider from the broom shop.

And they skipped school at 11 p.m. to walk to Potter Park to swim, recalls Clarence Horton, former supervisor of Michigan’s blind concession stand operators. The boys had “a standing rule that worked on everything.”

The superintendent at the time admired their spunk. Some of the pranks he tolerated would cause a statewide scandal nowadays.

THE BOYS pitched an unpopular principal, dressed in his best wedding suit, into a bathtub of cold water. When every boy in school confessed to the crime, the superintendent just took their senior dance away.

Life wasn’t all fun, though.

Several graduates mention one administrator who beat and taunted the orphans, illegitimate children or “people from the Southeastern part of Europe.”

When Lillian Hart, now 95, went to the school as a teacher in 1918, it was still “an institution.”

The school dressmaker had one pattern and dressed the state wards – orphans – alike in Indianhead cotton uniforms and sateen bloomers, Miss Hart and Clarence and Agnes Horton recall.

“You could tell the girls on the state.” Horton said. “They didn’t do that to the boys. They took them to Kositchek’s” clothing store.

When “a child from a loving home” entered MSB, Mrs. Sawyer could “smell the difference.”

“He had another dimension from us. He smelled different, of nice clothes and Ivory soap.”

“WE DIDN’T have the confidence that blind children do now. We were more institutionalized.”

By the 1920’s, the school was loosening up a bit. Radios expanded the children’s world, Miss Hart recalled. She lived at the school as a geography teacher until she retired in 1946 and moved to West Michigan Avenue.

By the time Mrs. Horton became an MSB music teacher in the 1930s, the Lions Club Auxiliary was providing used clothing for the orphans.

Another big change occurred when the school convinced Michigan State College professors that blind students were as mentally able as the sightless.

An even bigger change occurred when the school began helping its graduates find jobs in the late 1950s and 1960s, Mrs. Horton recalled.

Mrs. Noland got a teaching certificate from MSC, for example. But no school district would hire a blind teacher. Her younger brother Harold, also blind, was hired by Lansing School District only because a West Junior High teacher befriended him. Harold, who still teaches at Everett High, was one of the first blind teachers in Michigan.

For many children, MSB was their only chance for an education.

Few school districts outside big cities like Detroit and Grand Rapids had classes for blind students.

When Agnes Horton’s parents moved from Chicago to Michigan in 1918, they left six-year-old Agnes in a boarding house so she could attend Chicago’s only school for the blind.

SHE WENT crosstown daily on a street car. A policeman and a student hired for the purpose met her at the two transfer points. When she moved to the Michigan School for the Blind at aged eight, it seemed more like home.

Teachers were dedicated and tried to alleviate the institutional atmosphere with little personal touches, Mrs. Horton recalls.

She liked the matron who dabbed each girl with a drop of perfume before marching them off to church on Sundays.

Early teachers weren’t trained to teach blind children, however. When Miss Hart came in 1918, it was “just another teaching job,” she thought. Braille was “really Greek to me.”

Later she was one of the few teachers to learn to read Braille.

Hired for $40 a month – the same wage teachers received when the school opened in 1880 – Miss Hart worked day and night, and Saturday and Sunday.

“Most teachers stayed only a couple of years, got married or moved on,” Miss Hart said.

AMERICANS TODAY understand handicaps better, Mrs. Sawyer thinks.

At the time, though, the school pleaded with parents to treat their blind children like “normal youngsters.”

Now, as Mrs. Sawyer complains, they’re treating blind children so normally that they’re taking them out of the Michigan School for the Blind and putting them in regular public schools.

And she and her schoolmates don’t approve one bit.

*

Note: In 1994, the Michigan School for the Blind closed in Lansing and merged with the Michigan School for the Deaf in Flint.

*

My name is Rodney Shaw i went to MSB From Friday April23,1973 to October 14,1977 Dr. Bryant was the Driving Force behind the closing of MSB She was hired to find a way to close MSB IN 1975 When She became Superintendent of MSB The first thing she did was to cancel our Spring Break wich caused MSB one of it’s finest Teachers in 1975 Dr. Bryant had a Feasability Study from Minesota to figure out how to close MSB we students were left in the dark so to speak but we found out some how The different Governors of the State of Michigan tried several times to close MSB They finally did on October 1,1995Then the State of Michigan Let MSB be used for things it shouldn’t be used for and then with in the last year or more they Tore down Half of the MSB Buildings at MSB and they still want to put houses and apartments on MSB Campus The People that are Developing MSB will not let the MSB Students have any space on MSB For our Selves It’s Our School after ALL

Rodney Shaw MSB 1973-1977